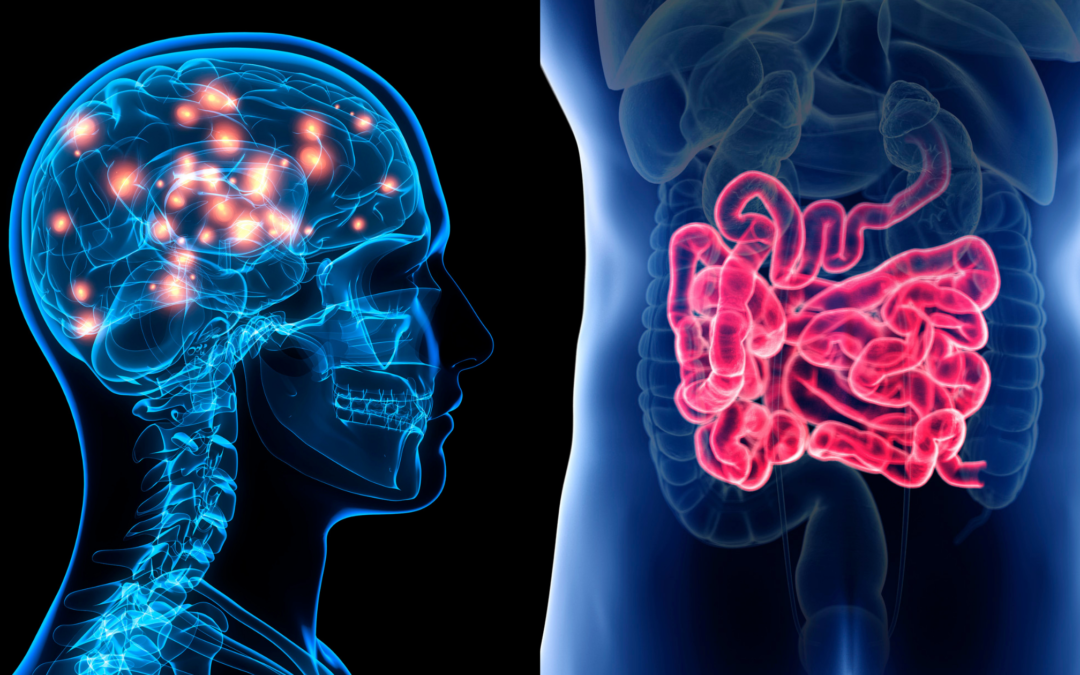

Stroke and Gut: There’s a Connection

I have a sensitive stomach, and ever since my stroke, more sensitive, which I didn’t think was possible. I wanted to know WHY! In other words, is there a connection between stroke and gut?

Harvard researchers found stomach problems could be linked to after-stroke stress. In fact, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is sensitive to anxiety, anger, depression, and sadness, too (all of which I’ve had post-stroke), and it can trigger symptoms in the gut. Therefore, the brain reflects what the GI system feels. Stress is the worst, the researchers concluded. (Fun fact: I used to consider giving a stressful TED talk about stroke; I’m not anymore).

A study involving mice, published this week in Nature Medicine, argues that striking the correct microbial balance could prompt changes in the immune system that would be likely to reduce brain damage after a stroke.

Researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center wanted to find out whether they could shift the balance of these cells to favor beneficial cells by meddling with the mouse bacteria.

So one group’s intestinal makeup was resistant to antibiotics and the other group bacteria was susceptible to treatment. When the latter group was given a combination of antibiotics over the course of two weeks, the microbes underwent change. Then the researchers obstructed the cerebral arteries, inducing an ischemic stroke [the most common type of stroke]. They discovered that the resultant brain damage was 60 percent smaller in the drug-susceptible mice.

Finally and painstakingly, the researchers took the colons of mice that had ischemic stroke and transplanted to new mice with no antibiotics, thus establishing a group with finagled gut bacteria but no drug exposure, and discovering that these mice had also acquired protection against stroke.

“These cells determine what kind of inflammatory immune response the brain is going to experience after stroke,” says neurologist Constantino Iadecola, director of the Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell and one of the study’s authors. “Immune cells end up helping out instead of contributing to the damage that occurs.”

A mouse’s genetic material is quite different from that of a human, and researchers will need clinical data, but at least they’re trying.

“This is just the beginning,” says Ulrich Dirnagl, a neurologist at the Center for Stroke Research Berlin who read the results. “The study links the microbiota and the immune system and the brain in stroke—an acute brain disorder—in one story. That’s really novel.”

That it is, Dr. Dirnagl. That it is.

Stroke patients were evaluated for common gastrointestinal symptoms including type and site of stroke admitted over an 18-month period with symptoms of vomiting, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), constipation, masticatory difficulties (including the muscles of the lips and tongue and the vascular and nervous systems supplying these tissues), and sialorrhea (drooling or excessive salivation), among others.

There was no significant difference in GI symptoms in either sex, site or type of stroke, except that constipation and incomplete evacuation were commoner in ischemic stroke.

The American Academy of Neurology says that people who have GI bleeding after stroke are more likely to die or become severely disabled than stroke survivors with no GI bleeding.

“This is an important finding since there are effective medications to reduce gastric acid that can lead to upper gastrointestinal bleeding,” said study author Martin O’Donnell, MB, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “More research will be needed to determine whether this is a viable strategy to improve outcomes after stroke in high-risk patients.”

The study focused on 6,853 people who had ischemic strokes, and of those, 829 people died during their hospital stay and 1,374 died within six months after the stroke.

A total of 100 people had gastrointestinal bleeding while they were in the hospital. In more than half of the cases, the GI bleeding occurred in people who had less severe strokes. Of those with GI bleeding, 46 percent had died within six months, compared to 20 percent of those without GI bleeding.

The study was supported by the Canadian Stroke Network, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and the University Health Network Women’s Health Program in Toronto.

The post Stroke and Gut: There’s a Connection appeared first on The Tales of A Stroke Survivor.